By Paolo Minieri

Are close-ups of gemological inclusions actually works of art, painted by Mother Nature in anticipation of our creative human inspirations?

Above you see an image captured by good friend of mine, the Neapolitan photographer Geppi Imperatore. Beneath it I placed Jackson Pollock’s Full Fathom 5. Then I gave him a call: “Geppi, your picture looks familiar to me…Who painted, who photographed?”

“Pollock was some million years late”, Geppi said.

It’s a somewhat provocative comparison that shows how quartz hydroxides can make a better work than color paints.

Earthborn art

This is not the first time gemologists have rummaged through the mysterious spaces of crystals and wound up being so surprised by the images produced that they ask themselves whether they’ve stepped into another area, the field of real art. When, after printing them, these photos become tangible objects like paintings, any human being will fall into a kind of aesthetic trance.

As far back as a couple of millenniums ago the great Latin naturalist Pliny the Elder said that the beauty of gemstones contained an explicit invitation to contemplation. Yet, in his contemplation, I doubt he owned a microscope or even a good camera. He worked using only his naked eyes. For sure, he didn’t WhatsApp any images like Geppi did, though in my contact list I’d much prefer Pliny’s name instead of a number of annoyers.

Now where Pliny thought nature was orderly and easy to understand, that principle seems to break down in more modern art. Oh, I know what happened in recent times to figurative painting. Artists got bored of portraying the usual Madonna holding baby Jesus and started depicting frantic abstract forms, red skies, green lakes, blue snow, geometric reversals, cubic faces, changes of perspective. Then, when they didn’t know how the hell to shock the poor people passing by their galleries anymore, they began to stab canvases. I don’t believe, according to ever-changing gemstone cutting styles, that gems will get stabbed too – although it would ironically bring back into play many inept gem-cutters I’ve happened to come across.

But I do love modern painters, and so I always keep in my mind Piet Mondrian’s essential squares. Abstract shapes, you know, sometimes emerge with no associated name.

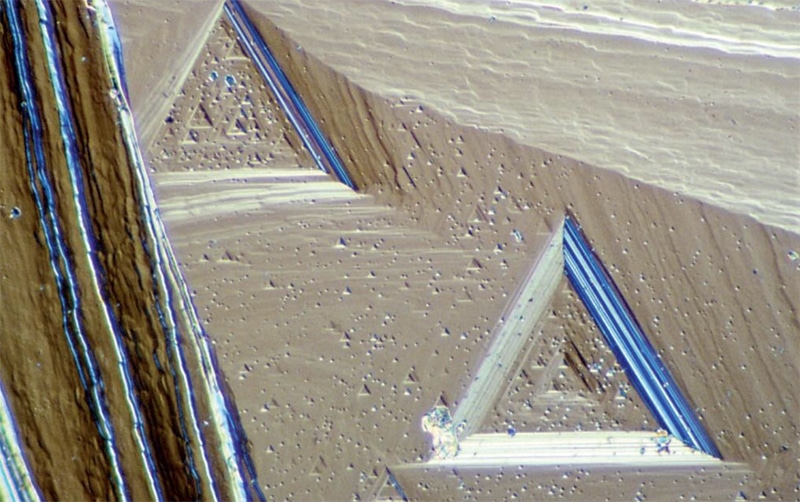

And so I run to my books and retrieve a picture shot by a true pioneer, the Italian gemologist Willi Andergassen, who passed away in 2001. A perfect geometry, captured in the form of these beautiful trigons inside a diamond; a mysterious carpet of perfect triangles.

And doesn’t Mondrian himself, in the composition below, evoke the co-planar, iso-oriented pattern of banded tubular or needle-like inclusions found in several gemstones? In any case it’s worth keeping in mind that the most intelligent form of life at the time trigons formed a diamond was probably constituted by algae unfit to handle palette, easel and paint-brushes.

In short, if you install a good camera on your microscope and observe certain inclusions carefully you can save yourself the price of admission to many art galleries. But since my microscope is locked in my office and a damned virus is confining me to an apartment I’ve got to stay quiet and write.

Then after, I’ll go to the Museum.

Paolo Minieri is a graduate in foreign literature and researcher in the Department of Geography at “L’Orientale” University in Napoli. An IGI Graduate Gemologist, Paolo serves as President of the Association of IGI Gemological Schools in Italy. He is the founder and editor of the Italian Gemological Review and a member of the Italian Gem Traders Association as well as the Ethical Committee of Assogemme.